Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

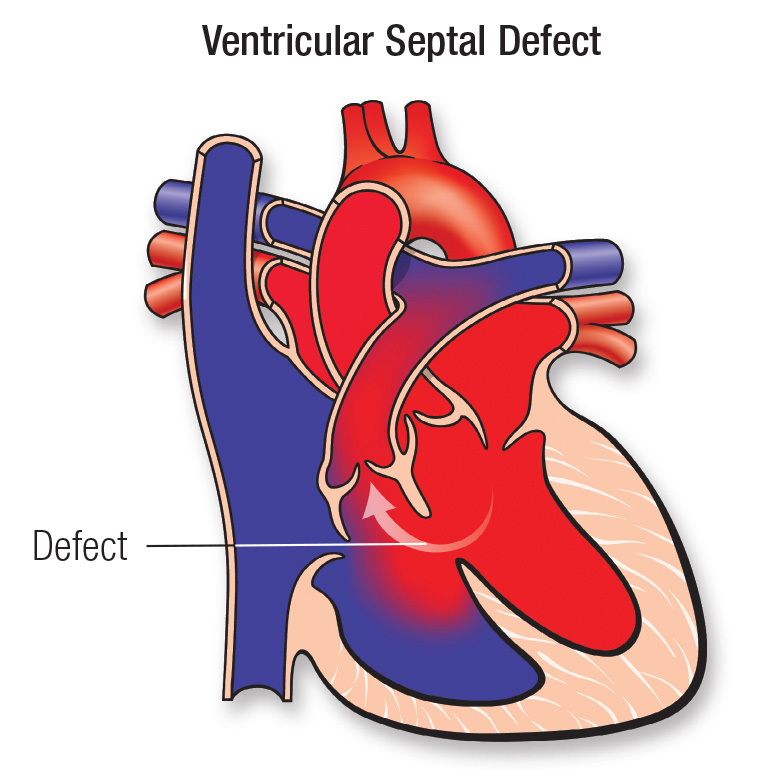

Normally, the heart has two sides, which are separated by a muscular wall called the septum. Each side of the heart also has two parts — the upper chamber, called an atrium, and the lower chamber, called a ventricle. The right side of the heart carries deoxygenated (bad/ impure) blood back into the heart and the left side carries oxygenated (good/ pure) blood back out to the body. A ventricular septal defect (VSD; also one of the “hole in the heart”) is an opening in the partition between the hearts two lower chambers (called the ventricles).

Patients with a small VSD usually do not have any symptoms. However, when the VSD is large, there is a large volume of “good” blood going back into the lungs instead of to the body. As a result the heart size enlarges and it has to work harder to pump enough blood into the body. Sometimes children with a VSD also have other heart abnormalities.

A child with large VSD may exhibit symptoms such as:

A VSD might be diagnosed before your babies birth using fetal echocardiogram (it is similar to a sonography study done on the abdomen, except here the fetus’s heart is studied).

A VSD can also be diagnosed soon after birth. Your baby may exhibit symptoms or your doctor might notice a heart murmur. Sometimes, a VSD isn’t diagnosed until your child is older.

Diagnosis of a ventricular septal defect may require some or all of these tests:

It’s important that a VSD be diagnosed early and treated when indicated to prevent permanent damage to the arteries in the lungs. Occasionally small VSDs also may need closure in order to prevent damage to neighboring valve.

Treatment for a ventricular septal defect also will depend on your child's health and on the size of the VSD. We may wait to see if the VSD will close on its own. Many small VSDs will do so before your child is 2 years old.

Infants with large VSDs will be put on medicines as well as have higher-calorie feedings to help with the symptoms as well as to allow weight gain.

During surgery to repair a VSD, a cardiothoracic surgeon will place a patch or stitches to close the hole during open heart surgery.

In certain cases, ventricular septal defects can be closed during a cardiac catheterization. During this procedure, we will insert a thin tube (catheter) through a vein and/or artery in the leg, and then guide it to the heart. A device is then inserted to close the VSD. This is typically done using both ultrasound (echo) and x-ray guidance to ensure appropriate device positioning and stability.

Because of enormous strides in medicine and technology, today most children with heart conditions go on to lead healthy, productive lives.

After a VSD repair, many children recover quickly and won't experience additional cardiac problems. They must see a Paediatric cardiologist for check-ups, and some remain on medicine. Very rarely, an additional surgery may be required.

If the child has other heart abnormalities, more follow-up care will be required.

We follow patients until they are young adults, coordinating care with primary care physicians.