Aortic Stenosis

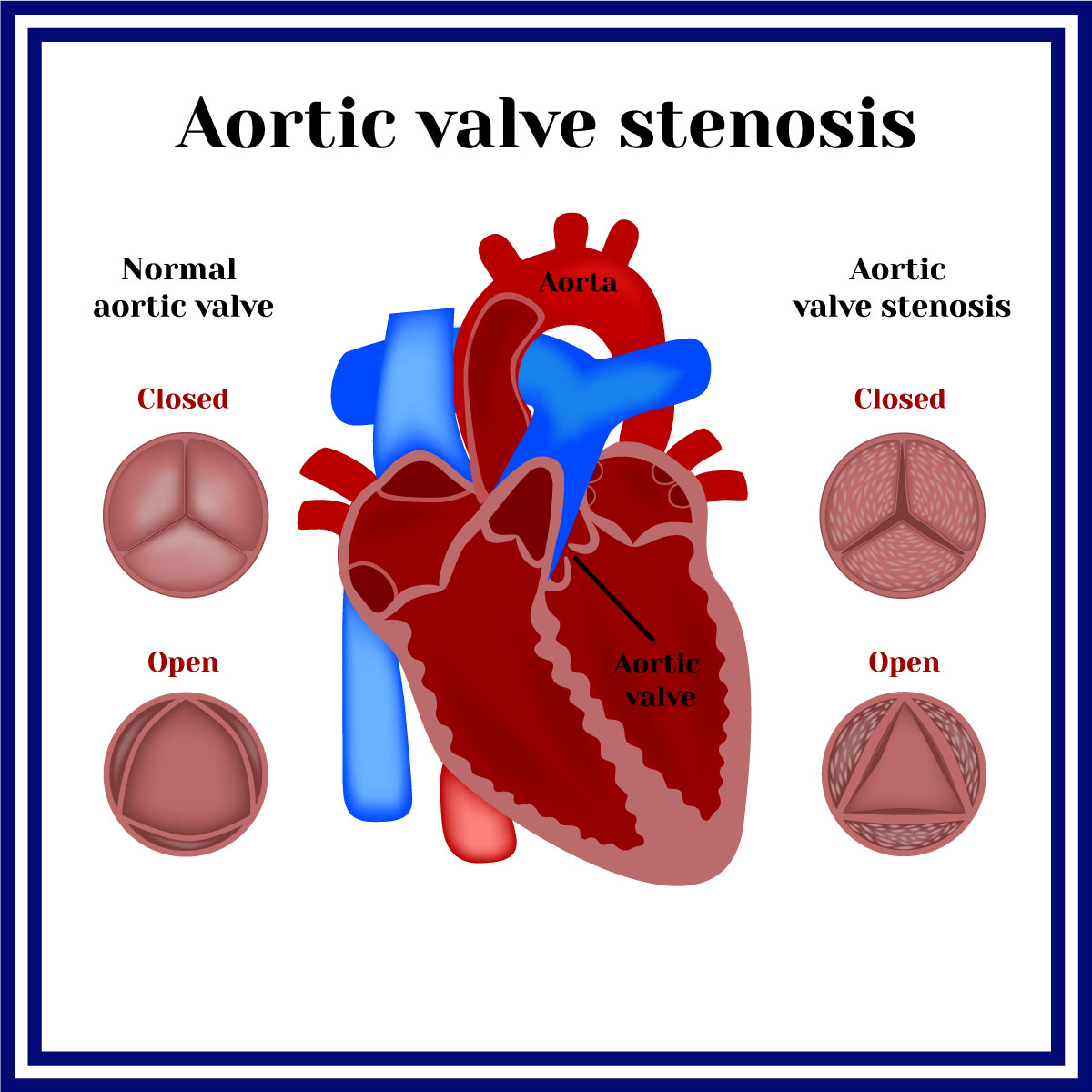

When the heart squeezes, the left ventricle (the lower left chamber) contracts, pushing blood into the aorta, the main artery that takes oxygenated (good/ red) blood to the body. The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and the aorta and prevents blood from leaking back into the heart between beats.

A normal aortic valve is made up of three thin leaflets. In congenital aortic stenosis (blocked aortic valve since birth) these leaflets are fused or are too thick. As a result, the aortic valve is too narrow and causes obstruction to blood flow out of the heart. The heart has to work harder to pump enough blood to the body. Aortic stenosis can be trivial, mild, moderate, severe or critical.

Sometimes the stenosis is below the valve in the left ventricle, caused by a fibrous membrane or a muscular ridge. This is called Subaortic stenosis. Also, the stenosis can occur above the valve, in the aorta itself; this is called Supravalvar aortic stenosis.

In young infants, severe or critical aortic stenosis can cause decreased blood flow, which causes symptoms such as a lack of energy (lethargy), poor feeding and respiratory distress. Milder forms of aortic stenosis usually won’t cause symptoms in infants or small children. As the child gets older, signs and symptoms of aortic stenosis may appear, including fatigue, a heart murmur (an extra heart sound when a doctor listens with a stethoscope), or, rarely, chest pain, fainting or arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythm).

In rare cases, newborns have critical aortic stenosis, which requires immediate medical attention. Sometimes these severe cases are diagnosed before birth, through fetal echocardiograms.

In most cases, we diagnose aortic stenosis after a primary care doctor detects a heart murmur and refers a child to us. Diagnosis may require some or all of these tests:

Aortic stenosis can run in families, so be sure to tell us if there is a history of a heart murmur in other close family members.

The exact treatment required for aortic stenosis depends on each child's heart anatomy. Trivial and mild aortic stenosis typically do not require treatment. Moderate, severe and critical aortic stenosis, however, do require treatment.

Cardiac catheterization

In most cases, the condition is treated with balloon valvuloplasty, which requires cardiac catheterization. We will insert a thin tube (catheter) into an artery in the leg, then guide the tube across the aortic valve and into your child’s heart.

The catheter will have a balloon on the end of it. The balloon will be briefly inflated to open up the narrow valve, then deflated and withdrawn. Sometimes, two catheters and balloons are used. In newborns, the blood vessels in the umbilical cord are sometimes used as the site where the catheters are inserted and advanced toward the heart.

Older children will spend one night in the hospital after this procedure, before returning home. They will also need to rest for the next few days, but then can resume normal activity. Newborns with critical conditions or children who are already inpatients may stay in the hospital slightly longer, either in the Intensive Care Unit or the ward.

Valvuloplasty surgery

Surgery to repair or to replace the valve is often necessary in severe cases. Depending on the age, gender and particular needs of your child, as well as the valve anatomy, surgeons may attempt to repair the valve, or at least improve its function, with a surgery called a valvuloplasty.

Artificial valves

Another option to treat aortic stenosis includes the use of mechanical (artificial) valves as replacement valves. If this is the case, your child may need to stay on blood-thinning medicines for the rest of his or her life.

Ross Procedure

Yet another option to treat aortic stenosis is the Ross Procedure. In this operation, the aortic valve is replaced with the patient’s pulmonary valve. The pulmonary valve is then replaced with one from a donated organ or an artificial one. This procedure allows the patient’s own pulmonary valve (now in the aortic position) to grow with the child.

Subaortic and supravalvar stenosis treatment

Subaortic and supravalvar stenosis do not respond to balloon dilation, and will require surgery if the amount of obstruction is moderate or severe, or, with subaortic stenosis, if the aortic valve begins to leak significantly. Surgery for subaortic stenosis involves cutting out the ridge. Surgery for supravalvar aortic stenosis involves enlarging the aorta with a patch.

Because of enormous strides in medicine and technology, today most children with heart conditions go on to lead healthy, productive lives as adults. All patients with aortic valve disease will need some form of lifelong follow-up care with a cardiologist.

Children with aortic stenosis require regular check-ups with a Paediatric Cardiologist. Some children must remain on medicine and limit physical activity.

As a child with aortic stenosis grows, blood may begin to leak through the abnormal valve. This is called aortic regurgitation or aortic insufficiency. In other children, the stenosis can reoccur. When this happens, balloon valvuloplasty can be repeated, as long as there isn’t significant aortic regurgitation. In severe cases, additional surgery may be necessary. We follow patients until they are young adults, coordinating care with the primary care physicians.