Cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle (myocardium). The muscle becomes abnormally thick, stiff or enlarged, affecting the heart’s ability to fill or pump blood and maintain its rhythm.

There are different types of cardiomyopathies, including:

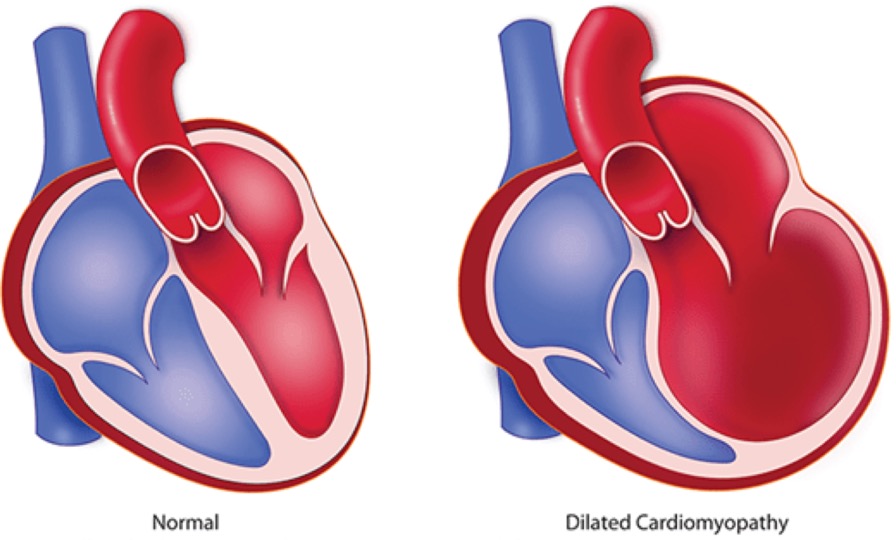

Dilated cardiomyopathy: The most common type in both adults and children. It results when the pumping chambers (ventricles) of the heart are abnormally enlarged and weakened. Some children who have a dilated heart have no symptoms, while others develop heart failure (difficulty breathing, difficulty eating, excessive sweating and poor growth). There are many different causes of dilated cardiomyopathy. In many cases it can develop after a viral infection of the heart (myocarditis). In other cases there could be underlying metabolic causes like deficiency of Vitamin D3/ Calcium. Some families have many members, across many generations, with this type of cardiomyopathy, which is known as familial dilated cardiomyopathy.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy :Occurs when one or more pumping chambers (ventricles) in your child’s heart become unusually thickened or “muscle-bound.” This may affect the left ventricle, which pumps blood to the body, or both the left and right ventricles (the right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs). This type of cardiomyopathy is often associated with abnormal heart rhythms, which can lead to sudden death. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may run in families; members of affected families are encouraged to undergo screening.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy : The rarest type of cardiomyopathy in children. The chambers of the heart become stiff, resulting in improper heart muscle relaxation, so that your child’s heart cannot fill with blood adequately. Abnormal heart rhythms may also occur with this disease. There are no medicines that are known to improve patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy, and a heart transplant is often recommended for children with this condition.

Noncompaction cardiomyopathy : Characterized by a spongy appearance of the heart muscle on echocardiography. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy is thought to be caused by incomplete heart cell maturation. It can exist alone or along with structural heart disease; it can be part of an underlying syndrome or occur idiopathically (with no identifiable cause). The heart with noncompaction can be dilated with decreased pumping function as in dilated cardiomyopathy (see above) or can have normal pumping function. The pumping chambers can also become thickened similar to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (see above). This is the most variable form of cardiomyopathy in that when diagnosed at a young age, children may be ill from having a poorly functioning heart, while noncompaction cardiomyopathy can also be found in older children and adults who have not developed any symptoms of abnormal heart function.

In some cases the heart of a child who has a cardiomyopathy will become progressively weaker and the child will end up in a stage of heart failure (difficulty breathing, difficulty eating, excessive sweating and poor growth) advanced enough to require transplantation. However, in some cases, cardiomyopathies can be treated with medications and the child’s health may improve.

When children develop cardiomyopathies, there is often not an identifiable factor such as another illness. Sometimes the cardiomyopathy is inherited (passed down through families because of a genetic difference).

More rarely in children, the cause of cardiomyopathy is identifiable. A heart infection called myocarditis, a protein abnormality in the heart muscle, chemotherapy drugs, metabolic disorders or muscle disorders are among the factors that can cause cardiomyopathy in a child or teenager.

Sometimes, particularly when adults develop cardiomyopathies, the disease is caused by factors such as diabetes, a previous heart attack or certain chemotherapy drugs. However, in many cases, in both adults and children, doctors don’t know what causes cardiomyopathies.

Symptoms of cardiomyopathy vary widely in type and severity. Sometimes infants have symptoms of cardiomyopathy shortly after birth. They can include:

Sometimes symptoms don’t appear until the child is older. They can include:

Diagnosis of cardiomyopathy may include:

If one person in a family is diagnosed with a cardiomyopathy, it may become important that a cardiologist evaluates other family members to assess their risk.

The treatment options for cardiomyopathy vary widely depending on the type and severity of the cardiomyopathy.

Medicines

Depending on the type of cardiomyopathy, we may prescribe medicines that help decrease the size of a dilated heart, relax the heart, increase the pumping strength, regulate the rhythm of the heart, or help in some other way. Often several medications are used in combination.

Pacemakers and implantable defibrillators

These devices help control the heart rhythm so the heart doesn’t beat too slowly or in an irregular pattern. The devices are implanted under the skin and connected to the heart with tiny wires called leads.

Septal myectomy

In patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), sometimes the septum (the wall of tissue that divides the two sides of the heart) bulges into the left ventricle (the lower, pumping chamber). If the person with HCM is having symptoms that are not helped by medications, a surgeon can remove the bulging portion of the septum through a surgery called septal myectomy. This surgery is rarely used.

Heart transplant

When symptoms that interfere with daily activities or growth in infants, or physical changes, result from a cardiomyopathy, heart transplant may be considered.

Children and teenagers with cardiomyopathies will continue to see a paediatric cardiologist regularly. The level of care will vary depending on the severity of the cardiomyopathy. Many benefit from consultation with a specialist in cardiomyopathy and may be referred to other specialists in metabolism, genetics, and or neurology, if an inherited or systemic disorder related to cardiomyopathy is suspected.

If a genetic cause of cardiomyopathy is suspected, it is important for other close family members (parents, siblings, children) to have their hearts checked by a cardiologist, to ensure that they do not have the same or a related heart condition (even if they do not have any symptoms of heart problems).