Atrioventricular Defects

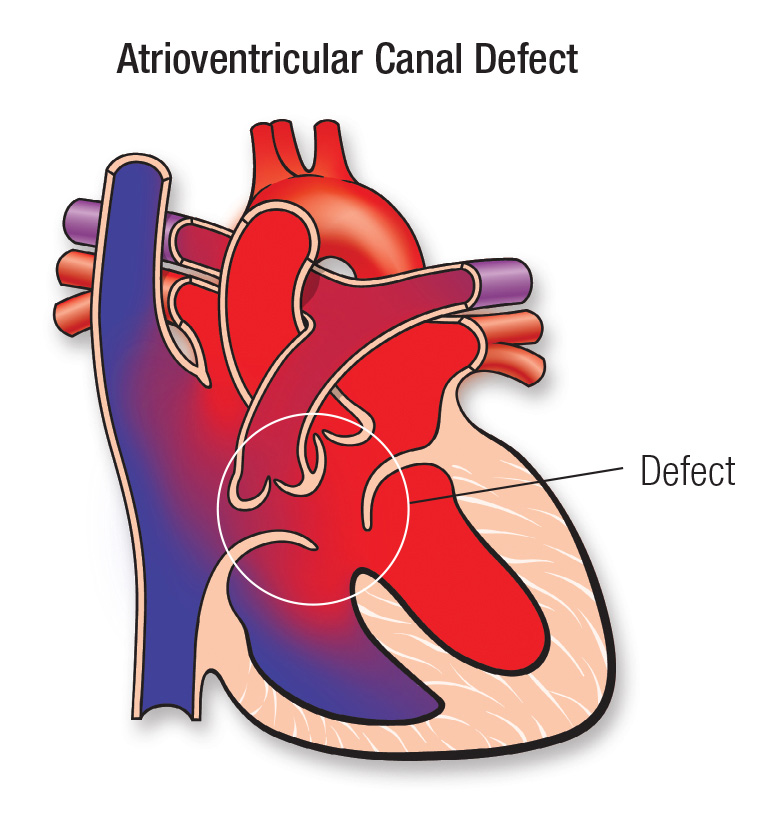

An atrioventricular canal defect is a problem in the part of the heart that connects the upper chambers (atria) to the lower chambers (ventricles). There are two main types of atrioventricular canal defects: Complete and Partial.

Complete atrioventricular canal (CAVC)

Complete atrioventricular canal (CAVC) is a severe congenital heart disease in which there is a large hole in the tissue (the septum) that separates the left and right sides of the heart. The hole is in the center of the heart, where the upper chambers (the atria) and the lower chambers (the ventricles) meet.

As the heart formed abnormally, the valves that separate the upper and lower chambers also developed abnormally. In a normal heart , two valves separate the upper and lower chambers of the heart: the tricuspid valve separates the right chambers and the mitral valve the left. In a child with a complete atrioventricular canal defect, there is only one large valve, and it may not close correctly.

As a result of the abnormal passageway between the two sides of the heart, blood from both sides mixes, and too much blood circulates back to the lungs before it travels through the body. This means the heart works harder than it should have to, and will become enlarged and damaged if the problems aren’t repaired.

Partial atrioventricular canal defect is the less severe form of this heart defect. The hole does not extend between the lower chambers of the heart and the valves are better formed. Usually it is necessary only to close the hole between the upper chambers (this hole is called an atrial septal defect, or ASD) and to do a minor repair of the mitral valve.

In a complete atrioventricular canal defect, the following symptoms may be present within

several days or weeks of birth:

Partial atrioventricular canal defects cause fewer symptoms and sometimes aren’t diagnosed until the child reaches his or her 20s or 30s. Then, he or she may begin to experience irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia), leaky valves or other effects.

Sometimes a complete atrioventricular canal defect is diagnosed on a fetal ultrasound and/or echocardiogram.

The paediatrician who evaluates your baby in the hospital might also make the diagnosis. Or a primary care paediatrician might notice a murmur and other symptoms and refer your child to a Paediatric Cardiologist.

Diagnosis of atrioventricular canal defects may require some or all of these tests:

Complete atrioventricular canal defects require surgery, usually within the first two or three months of life. The surgeon will close the large hole with one or two patches. The patches are stitched into the heart muscle, and as the child grows, the tissue grows over the patches.

The surgeon will also separate the single large valve into two valves and will reconstruct the valves so they are as close to normal as possible, depending on the child’s heart anatomy.

Partial atrioventricular canal defects also require surgery, whether they are diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. The surgeon will patch or stitch the atrial septal defect closed. He will also repair the mitral valve or replace it with either an artificial valve or a valve from a donated organ.

Because of enormous strides in medicine and technology, today most children born with atrioventricular canal defects go on to lead productive lives as adults. After surgery, most children recover completely and won’t need additional surgery or catheterization procedures.

A child who has had surgical repair of an atrioventricular canal defect will require life-long care by a cardiologist.

We follow patients until they are young adults, coordinating care with the primary care physician. Patients will need to carefully follow doctors’ advice, including staying on any medications prescribed.

Sometimes children with an atrioventricular canal defect experience heart problems later in life, including irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) and leaky or narrowing valves. Medicine, additional surgery and/or cardiac catheterization may be required.